Easy Python speed wins with functools.lru_cache

Mon 10 June 2019 TutorialsRecently, I was reading an interesting article on some under-used Python features. In the article, the author mentioned that from Python version 3.2, the standard library came with a built in decorator functools.lru_cache which I found exciting as it has the potential to speed up a lot of applications with very little effort.

That's great and all, you may be thinking, but what is it? Well, the decorator provides access to a ready-built cache that uses the Least Recently Used (LRU) replacement strategy, hence the name lru_cache. Of course, that sentence probably sounds a little intimidating, so let's break it down.

What is a cache?#

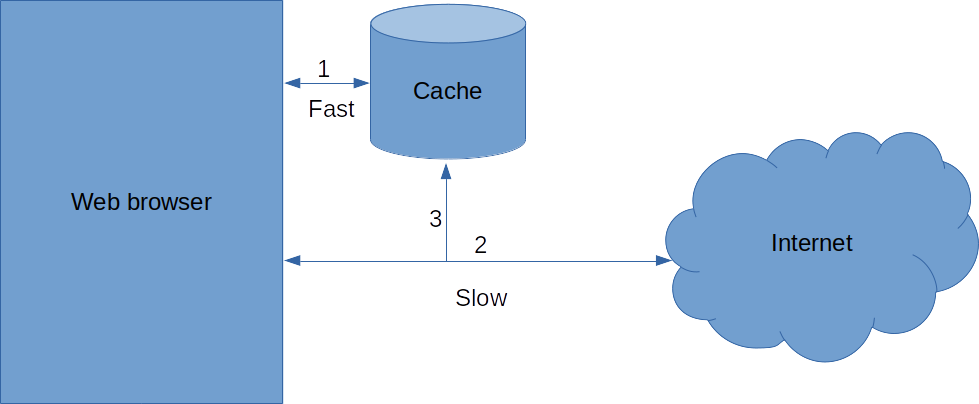

A cache is a place that is quick to access where you store things that are otherwise slow to access. To demonstrate this, let's take your web browser as an example.

Getting a web page from the internet can take up to a few seconds, even on a fast internet connection. In computer time this is an eternity. To solve this, browsers store the web pages you've already visited in a cache on your computer which can be thousands of times faster to access.

Using a cache, the steps to download a webpage are as follows:

- Check the local cache for the page. If it's there, return that.

- Go find the web page on the internet and download it from there.

- Store that web page in the cache to make it faster to access in future.

While this doesn't make things faster the first time you visit a web page, often you'll find yourself visiting a page more than once (think Facebook, or your email) and every subsequent visit will be faster.

Web browsers aren't the only place caches are used. They are used everywhere from servers to computer hardware between the CPU and your hard disk/SSD. Getting things from a cache is quick, and so when you are getting something more than once, it can speed up a program a lot.

What does LRU mean?#

A cache can only ever store a finite amount of things, and often is much smaller than whatever it is caching (for example, your hard drive is much smaller than the internet). This means that sometimes you will need to swap something that is already in the cache out for something else that you want to put in the cache. The way you decide what to take out is called a replacement strategy.

That's where LRU comes in. LRU stands for Least Recently Used and is a commonly used replacement strategy for caches.

Why does a replacement strategy matter?

A cache performs really well when it contains the thing you are trying to access, and not so well when it doesn't. The percentage of times that the cache contains the item you are looking for is called the hit rate. The primary factor in hit rate (apart from cache size) is replacement strategy. Think about it this way: Using the browser example, if your most accessed site was `www.facebook.com` and your replacement strategy was to get rid of the most accessed site, then you are going to have a low hit rate. However if it was LRU, the hit rate would be much better.

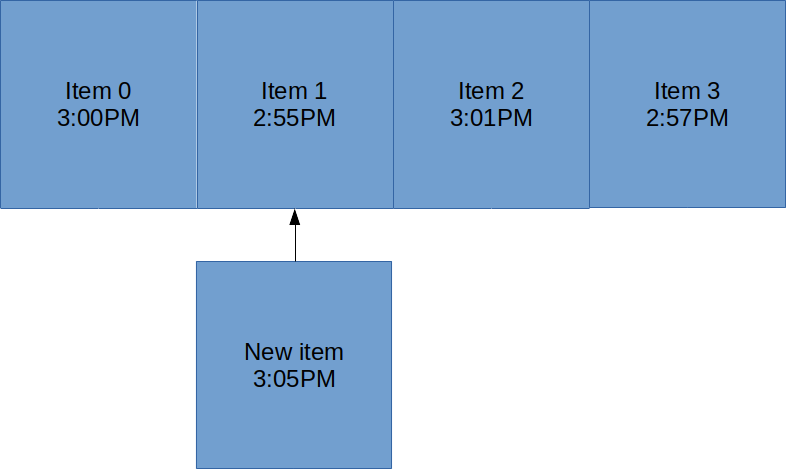

The idea behind Least Rececntly Used replacement is that if you haven't accessed something in a while, you probably won't any time soon. To use the strategy, you just get rid of the item that was used longest ago when the cache is full.

In the above diagram each item in the cache has an associated access time. LRU chooses the item at 2:55PM to be replaced since it was accessed longest ago. If there were two objects with the same access time, then LRU would pick one at random.

It turns out that there is an optimal strategy for choosing what to replace in a cache and that is to get rid of the thing that won't be used for longest. This is called Bélády's optimal algorithm but unfortunately requires knowing the future. Thankfully, in many situations LRU provides near optimal performance .

How do I use it?#

functools.lru_cache is a decorator, so you can just place it on top of your function:

import functools

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize=128)

def fib(n):

if n < 2:

return 1

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

The Fibonacci example is really commonly used here because the speed-up is so dramatic for so little effort. Running this on my machine, I got the following results for with and without cache versions of this function.

$ python3 -m timeit -s 'from fib_test import fib' 'fib(30)'

10 loops, best of 3: 282 msec per loop

$ python3 -m timeit -s 'from fib_test import fib_cache' 'fib_cache(30)'

10000000 loops, best of 3: 0.0791 usec per loop

That's a 3,565,107x speed increase for a single line of code.

Of course, I think it can be hard to see how you'd actually use this in practice, since it's quite rare to need to calculate the Fibonacci series. Going back to our example with web pages, we can take the slightly more realistic example of caching rendered templates.

In server development, usually individual pages are stored as templates that have placeholder variables. For example, the following is a template for a page that displays the results of various football matches for a given day.

<html>

<body>

<h1>Matches for {{day}}</h1>

<table id="matches">

<tr>

<td>Home team</td>

<td>Away team</td>

<td>Score</td>

</tr>

{% for match in matches %}

<tr>

<td>{{match["home"]}}</td>

<td>{{match["away"]}}</td>

<td>{{match["home_goals"]}} - {{match["away_goals"]}}</td>

</tr>

{% endfor %}

</table>

</body>

</html>

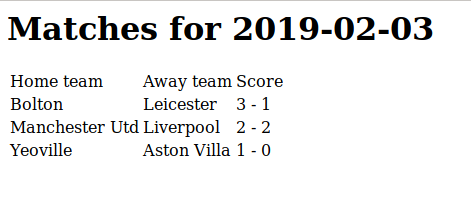

When the template is rendered, it looks like the below:

This is a prime target for caching because the results for each day won't change and it's likely that there will be multiple hits on each day. Below is a Flask app that serves this template. I've introduced a 50ms delay to simulate getting the match dictionary over a network/from a large database.

import json

import time

from flask import Flask, render_template

app = Flask(__name__)

with open('match.json','r') as f:

match_dict = json.load(f)

def get_matches(day):

# simulate network/database delay

time.sleep(0.05)

return match_dict[day]

@app.route('/matches/<day>')

def show_matches(day):

matches = get_matches(day)

return render_template('matches.html', matches=matches, day=day)

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run()

Using requests to get three match days without caching takes on average 171ms running locally on my computer. This isn't bad, but we can do better, even considering the artificial delay.

@app.route('/matches/<day>')

@functools.lru_cache(maxsize=4)

def show_matches(day):

matches = get_matches(day)

return render_template('matches.html', matches=matches, day=day)

I've set maxsize=4 in this example, because my test script only gets the same three days and it's best to set a power of two. Using this makes the average come down to 13.7ms over 10 loops.

Anything else I should know?#

The Python docs are pretty good, but there are a few things worth highlighting.

Built in functions#

The decorator comes with some built-in functions that you may find useful. cache_info() will help you figure out how big maxsize should be by giving you information on hits, misses and the current size of the cache. cache_clear() will delete all elements in the cache.

Sometimes you shouldn't use a cache#

In general a cache can only be used when:

- The data doesn't change for the lifetime of the cache.

- The function will always return the same value for the same arguments (so

timeandrandomdon't make sense to cache). - The function has no side effects. If the cache is hit, then the function never gets called, so make sure you're not changing any state in it.

- The function doesn't return distinct mutable objects. For example, functions that return lists are a bad idea to cache since the reference to the list will be cached, not the list contents.

Whilst it's not suitable for every situation, caching can be a super simple way to gain a large performance boost, and functools.lru_cache makes it even easier to use. If you're interested to learn more then check out some of the links below.

Cameron MacLeod

Cameron MacLeod